The Cleveland Browns lost a game to the Seattle Seahawks that before the game most fans thought would end that way. During the game, QB PJ Walker turned the ball over a ton, again, but the Browns still had a chance to win the game.

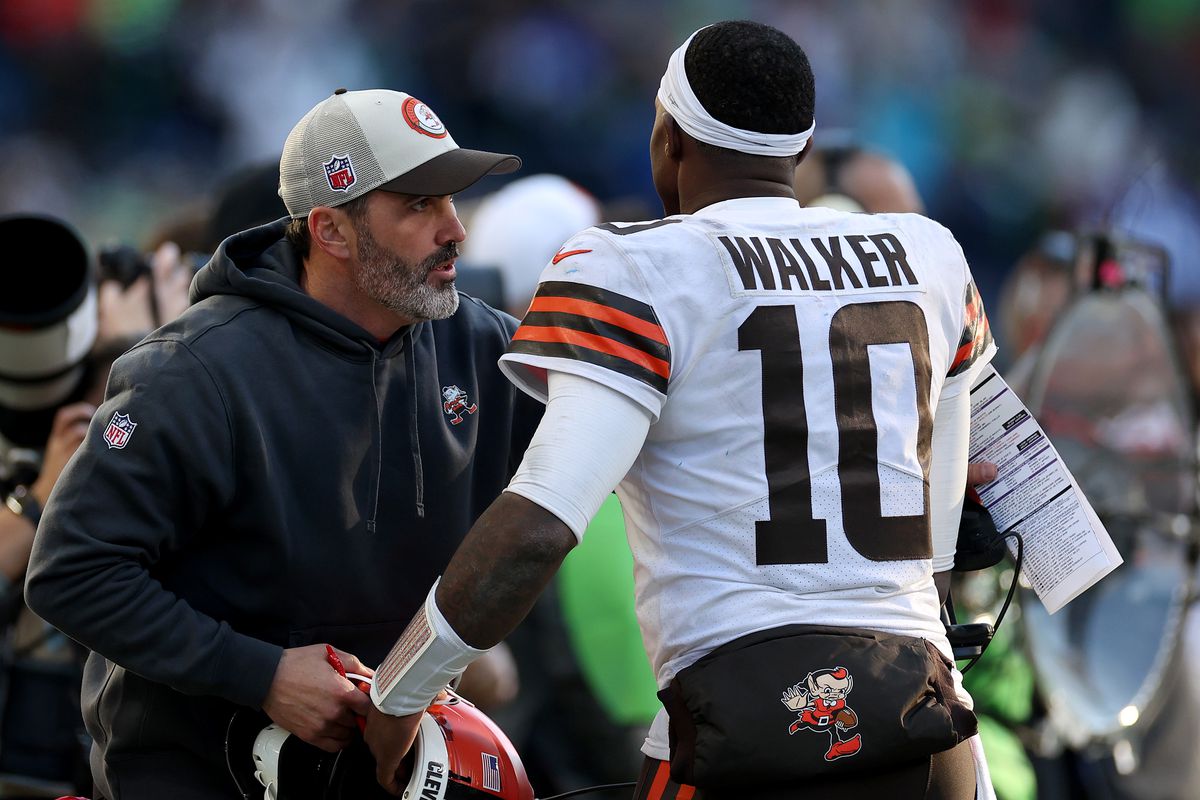

As has been beaten to a pulp by fans and media, HC Kevin Stefanski called a relatively low-risk quick slant pass to WR Amari Cooper to gain a first down and, basically, end the game. Instead, the pass went off a defender’s helmet, bounced way in the air and was intercepted.

Based on the outcome, Stefanski made the wrong decision according to many. Based on the outcome, the right decision was to run the ball and hope for the first down or punt it according to many.

The problem with the idea of a “right decision” in that context is that it assumes many things.

In the NFL, the reality is there is never a right decision until after the play is over (unless a team is kneeling out the clock for a victory). Every decision has some chance of creating an outcome that is desired and one that is not.

If Adams hadn’t jumped at the exact right moment and Walker’s pass was completed for a first down, Stefanski’s “decision” would have gone from wrong to right. The reason the word decision is in quotation marks is because that line of thinking doesn’t actually judge the decision, it judges the results.

Therein lies one of the reasons that the NFL is so interesting but so hard to evaluate. Just because something works doesn’t make it a great idea. Just because something doesn’t work doesn’t make it a bad idea. A great play call can get blown up because of a loose piece of sod on the field. A questionable call can work for the offense great because a defender slips or for the defense because the opposing quarterback doesn’t see a wide-open man.

Actual wrong decisions are far more limited than many would like to believe. Losing track of downs, sending 12 men on the field, forgetting to go down instead of scoring late in a game and whatever the Miami Hurricanes did to lose a certain win if they would have just kneeled it out are a few of the rare examples of wrong decisions.

Otherwise, the nuance is that we (including this writer with over a decade of professional experience covering the team) would be more accurate if we just stated whether a decision worked or not instead of assigning right or wrong labels. That seems to be less fun, less emotional and way too practical for the world we live in today.

In the end, teams and coaches will be judged by wins and losses. Context only matters so far. Cleveland lost in Week 8, dropping their record to 4-3. Without Nick Chubb, Jack Conklin and Deshaun Watson for most of the season, 4-3 should be seen as a good record but the evaluation doesn’t end until January.

For now, fans and media will continue to argue “right” and “wrong” decisions while the NFL schedule turns the page.

Loading comments...